Saiko! The Large Family: Gender and Class Analysis

This short article is going to look into a couple overlooked features of this Japanese horror mockumentary, in light of the YouTube video made by Reignbot.

Disclaimer

I actually placed a rough analysis in the comment section of Reignbot’s video, but since it’s the first time in a while I’ve written an extensive piece, I’ve decided to transfer a neater version here.

A couple things before we delve into this: this is by no means a fleshed-out exploration, just some ideas I had. In addition, I’ve only watched footage from Reignbot’s video. For sure, anyone looking to analyse this mockumentary properly will benefit from watching the original. Keep this in mind as you read. I plan on watching the original video as well as the other ‘episodes’ in the future. Finally, this article will include spoilers; I assume in reading this you have watched the video, or that you are fine in being spoiled. The article will most likely only make sense if you’ve watched the video. Here it is:

Saiko! The Large Family

What I have in common with modern horror film-makers is a longing for a more ‘authentic’ form of capturing reality, in a digital age of beauty filters and smooth edges. If not executed properly, I feel as if horror media is at risk of becoming more ‘gimmicky’ the higher the production value is.

In fact, I fear that the internet’s current obsession with perfectly curated media will cause Horror as a genre to lose something of it’s essence. There is no room for a distaste of itchy sensations in Horror. What happened to the truly grotesque? There is something too ‘clean’ about the execution of cosmetics in film, the scarlet guts that cascade out of their paranormal victims. Uncanniness ought to be captured in the blurry peripheries of found footage, not in Dutch angle shots.

That’s not to say that modern horror media, with all it’s technological aids, is incapable of rendering great art. Not at all. Rather some people, including myself, long for something more than cheap jump scares, or the regurgitative crap you see pushed out too much nowadays, clogging up the space for the representation of real artistry.

With all this lingering in the back of my mind for a while now, I stumbled across Reignbot’s video on ‘Saiko! The Large Family’ (Saiko! For short). Released in 2009, the mockumentary hails back to a digital era of grainy footage and yellowy, dim lighting, that as a ‘05 child reminds me of the videos my parents filmed on their old Sony cameras. As an earlier form of analogue horror, ‘Saiko!’ naturally bears the quintessential stylistic aspects of the genre.

Bearing this in mind, I found both the video and it’s comments to overlook some crucial details related to the socio-economic context of the narrative - and how the elements of horror both serve as a potential allegory for - some ideas about the violence of poverty and stringent, oppressive gender roles.

The ‘true’ nature of ‘Saiko!’s narrative is ascertained through details, subtleties in the filming, the language, and the plot. No conclusions drawn about the potentially murderous mother is ever confirmed or explained. Yet the show perfectly maintains an awful, itchy feeling, like hot water boiling close to the surface. Nothing erupts. The mother does linger in windows and gaps in the doors, as the true ‘ghost’ of the house.

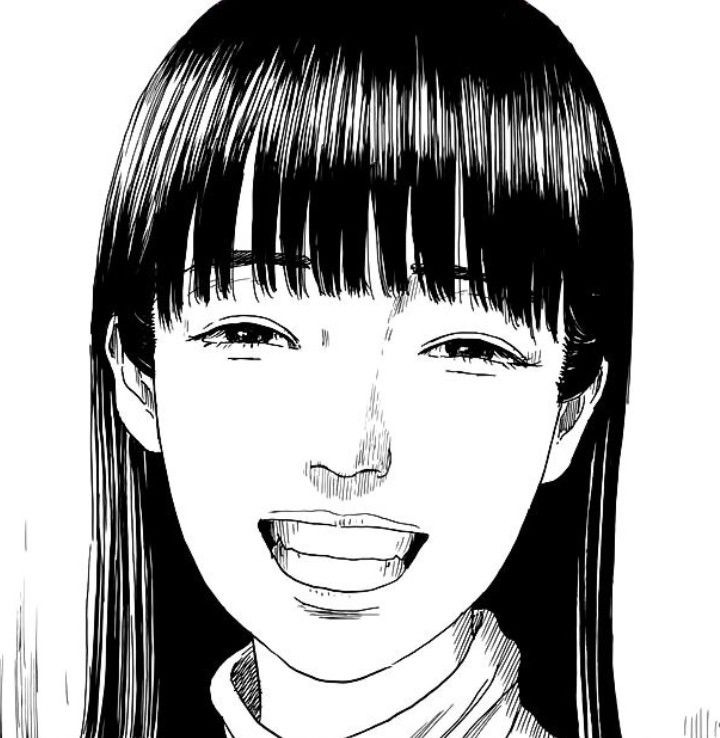

Many viewers came to the conclusion themselves that she was silently orchestrating all the ‘unfortunate’ deaths in the show. The symbolic use of the knives in the fruit-basket combines the traditional image of female domesticity and a nurturing disposition with an uneasy murderous intent. Personally this is not the first time I’ve encountered a maternal villain in Japanese media. The manga series ‘Blood on the Tracks’ has many intertextual similarities with ‘Saiko!’ The mothers in both stories wear a face that is not their own, an uncanny mask, and exhume silent rage. Both mothers also pass their trauma onto their children, roping them children in on their scheming and crimes and torturing them in the process, in a real subversion of traditional maternal instincts and expectations. Through the lens of gender, one may examine Japan’s societal expectations of the mother figure. She is expected to be dutiful, maintain both a career and family, and must remain sweet and gentle. For both characters, their villainy is inextricably linked to their failure to truly conform to this role.

Both mothers, however, truly have no power. Maintaining a passive façade is imperative to their survival in society.

Above: Seiko Osabe in ‘Blood on the Tracks’. Skip to 22:22 in Reignbot’s video to see the similarities in the mother’s expression.

Again, in ‘Saiko!’ nothing about the mother’s true evil nature is ever explicitly revealed, only inferred; it’s important to note, therefore, that powerless figures in media convey their rage and oppression through the use of symbolism. Such as the fruit basket, or the mother watching from the window. Where the mother does seem to have power is in domestic spaces. She violently lashes out at her children in the garden, where her first husband is presumably buried. In fact, the only thing she does nurture is the plants that grow above her husbands body. Reignbot conspires that as the mother cooks in the kitchen, she seasons the father’s food with poison. To gain leverage, mothers must move secretly, as they scream in agonised silence.

A hugely overlooked detail that is emphasised in ‘Saiko!’ - which is what compelled me to explore this angle of analysis in the first place - is that the documentary in the family took place because the interviewer was interested in the unusually large family, in a time where Japan was (and is still) undergoing a huge decline in birth rates. Of course this is linked to the declining economic position of Japan, and it’s declining standards of living. Having so many children is simply not viable in this case, and I use the word ‘viable’ deliberately. There is an immense pressure upon the mother to provide for her family. She is stuck in an impossible position where she has to work, yet she cannot, because she has to look after her children. Whilst Sumio (the current father) is clearly a benevolent man, it is his status as a man that has eased the mother from dire conditions she could hardly alleviate herself.

An interesting and unexplored angle to view the mother’s motivations is that she murdered members of her family for their life insurance. Her family is assailed by poverty: Ringo falls victim to a human trafficking ring, Sumio has to pull from his retirement fund to help her, and the jarring and often uninsightful interviewer even makes a point to mention that the family has to shuffle past each other to get by in the dining room. Approaching the show through the lens of class reveals the very real violence of poverty. Rather paradoxically, the mother is forced to kill her family in order to support them.

To conclude that this is the only motivation for the mother’s crimes would be reductionist and frankly, quite false. The show makes sure to include a nasty edge to her character, and there is a subtle, yet poignant paranormal dimension to the narrative through the mention of ghosts and ghost photography. However, I did feel as if a gender and class based exploration of the show was sorely needed and may encourage further discussion of analysis among those interested.